I’ve never been much of a Trekkie, but when my two favourite shows on Netflix, Better Call Saul and Ozark, aired their final episodes just within a few weeks’ time, I instinctively knew that a decade of reliably and deeply resonating entertainment would come to an end for me, too.

So in the past couple of weeks, on Tuesday nights when my wife is out for zumba class, I got hooked up to The Original Series, following the adventures of starship NCC-1701. Often, the 8 and 11 year olds watch along with me (and my hope is it will get them out from that magical fantasy wormhole the Weasley-industrial complex has dragged them into).

The fascinating thing about 1960s mass media science-fiction is the dialectic tense between those thoroughly humanistic, in context of cold-war nuclear fear even anthro-optimistic storylines and the way the production designers imagined 23rd century technology.

We intuitively snark about our grandparents’ ideas and images of the future, but I mean.. remember back in 2017, when the German market for voice-controlled smart homes was projected to triple by 2022?

So instead of making fun of our collective past selves, we could look for the details in the storylines, connect to our current reality, and be open to perhaps even learn something in the process.

Midway through the Original Series’ first season, in episode 17 first airing in January 1967, the Enterprise discovers Gothos, a rogue planet drifting through space, inhabited by an eccentric paradimensional being named Trelane, who uses his apparently unlimited power over matter and form to manipulate the crew.

Trelane’s eccentricism materialises in a strong interest in 18th century European aristocratic power structures and aesthetics, naming himself the Squire of Gothos and keeping the Enterprise crew hostage, albeit with a pronounced desire to impress them with his hospitality and playful entertainment. But something seems odd:

McCoy: “You should taste his food! Straw would taste better than this meat..and water is a hundred times better than this brandy, nothing has any taste at all”

Spock: “It may not be appetizing, doctor, but it’s very logical”

McCoy: “Well, there’s that magic word again” 🙄

Spock: “This simply means that Trelane knows all the forms, but none of the substance”

When thinking about the Trelane character, there are two themes which at closer inspection connect to an interesting dialectic in our present state of world:

the mythological Trickster archetype, and its perceived function as an innovator in our cultural evolution

the latest advances in statistical machine learning, especially in the field of Large Language Models, and the “eerie ventriloquism of smart systems that know nothing about the world, yet sound just like people who do”

The psychologist Norbert Bischof, in his 1996 masterpiece Das Kraftfeld der Mythen (‘The mythological field of forces’), points to the anthropological observation that the two essential archetypes, the Hero and the Trickster, can be identified in the narrative traditions of all known cultures around the world, dating back to long before those cultures could have possibly made any contact with each other.

According to Bischof, this peculiar similarity in the structures of myths around the world arises from our species’ basic dynamics of biological, cognitive, and psycho-social development during childhood and adolescence. We share some of those dynamics with other social mammals, like playful curiosity for what’s beyond the known and comfortable (this is where Bischof’s Zurich Model of Social Motivation connects with Jaak Panksepp’s work on affective neuroscience).

While the Hero archetype expresses the process of individualisation in later adolescence on an explicit and rather predictable narrative arc of growth, the Trickster archetype is far more subtle: the pre-puberty child begins to understand that many of the stories and ideas they have grown up with are not real and as a consequence, realises that much of the world is made of conventions, norms, but also delusion.

This certainly is no walk in the park, existentially. As the child tries to navigate their epistemological and social environment, they generate what Bischof calls ‘assumptive realities’, not quite fictional but very simplified assumptions about the world around them, so it becomes more cognitively and psychologically computable for the child’s still developing ratio.

From this imbalance of experience and ratio the pre-puberty child develops coping mechanisms, resulting in a relatively higher affinity to jokes, slapstick, playing tricks, doing mischief, and openly questioning or disrupting authority - which essentially equals to exploring the boundaries of, and thereby testing hypotheses about the conventions and norms of the adults’ world.

The most notorious trickster figure in Western narrative tradition is Hermes, the ancient Greek deity able to move quickly and freely between the worlds of the mortal and the divine, between what is possible and what is not, understanding the boundaries between both, and often intentionally confusing their definition for his own playful entertainment or other childish motivations.

Hermes is considered the god of roads and travelers, thieves, athletes, shepherds, commerce, speed, cunning, wit, magic and sleep. This vast and rather complex characterisation suggests he is a very old archetype, most likely an adaptation of the Egyptian deity Thoth, god of the moon, wisdom, writing, science, magic, art, and judgment.

The Hermes/Thoth myth connects magic and science with the sophisticated use of language (Thoth is credited with the invention of the hieroglyphs, Hermes with the invention of what we today call alternative facts as well as the mastery of rhetorical persuasion), by making productive use of randomness: Hermes/Thoth invented the dices and learned to read from them the will of the gods, thus making comfortingly plausible sense from a seemingly random natural world.

5000 years after the first hieroglyphs were carved in stone, today we are looking again, in collective awe and wonder, at a new master of persuasive rhetoric which is very likely to disrupt our conventional norms and confusing the boundaries of what has previously been deemed impossible.

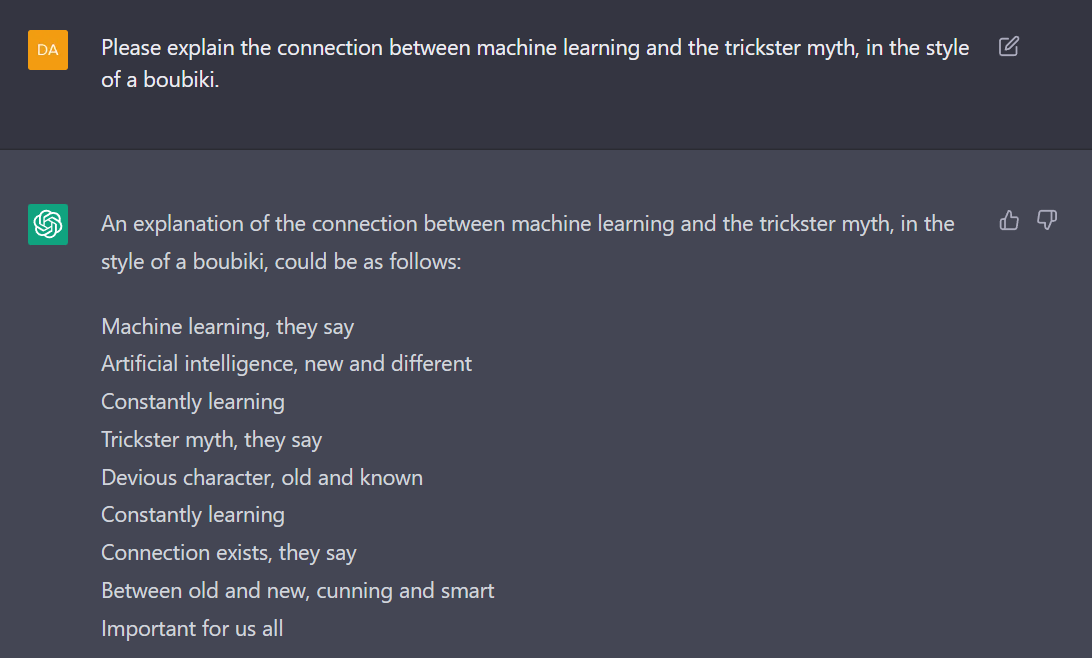

In December 2022, OpenAI released ChatGPT, an easy to use interface to the GPT-3 Large Language Model, and even the most die-hard machine intelligence sceptics like myself have to admit to be deeply impressed by the level of sophistication the deep learning algorithm seems showing when answering our queries - but why not let the machine introduce itself:

If this screenshot is your first encounter with ChatGPT, you might be impressed too, but that excitement will eventually fade as you spend more time with the interface and realise that, much like Trelane, the Squire of Gothos trickster in Star Trek, the model knows all the forms but none of the substance.

Gary Marcus, one of the leading researchers in the field of Artificial Intelligence, is also one of the most vocal sceptics concerning its hype:

“The impressive thing about GPT is that it spits out hundreds of perfectly fluent, often plausible prose at a regular clip, with no human filtering required…

When GPT sounds plausible, it is because every paraphrased bit that it pastes together is grounded in something that actual humans said, and there is often some vague (but often irrelevant) relationship between..”

The essential question I want to adress here is, where does this feeling of plausible vagueness originate? My intuition is, it’s not in the machine but ourselves.

Just like the pre-puberty trickster child, ChatGPT creates assumptive realities from our queries. But unlike the trickster child, the machine has no intrinsic motivation to understand, learn, and ultimately grow. Yet, just like the Egyptians and Greek projected deep meaning into their Trickster gods, we project meaning into the surface output of the deep learning interface. It takes two to tango.

The machine’s fundamental weakness is a lack of substance beneath the surface. Still, for many requirements in our present state of surface-industrial economy, this might be perfectly good enough. The machine’s greatest strength is our sufficiency with surfaces.

There is no doubt, the machine will keep getting better at appealing to our sense of plausibility, and this certainly will cause a disruption in the employment market for those roles (and more generally, kinds of personalities) whose primary resource value is to create and maintain surfaces, without any need or motivation to get at the substance.

And I can’t lie, I’m very much looking forward to this.

The big question of this decade will be which kinds of personalities, what configuration of social motivations in Norbert Bischof’s terms, are inherently best prepared to collaborate with the machine.

Important for us all.

Let’s keep constantly learning,

Daniel

***

PS. In case you are wondering wtf is a “boubiki”, it’s a kind of variable I co-created with ChatGPT for optimised plausible vagueness:

I like this line especially: "employment market for those roles (and more generally, kinds of personalities) whose primary resource value is to create and maintain surfaces, without any need or motivation to get at the substance"